When I first wrote this piece in 2019 for WBCSD, it was a hard time for science, admittedly. It became even harder with the COVID-19 pandemic afterwards.

5 years later, we’re still living in a world where nearly everyone we know carries around a tiny computer that can give you the answer to nearly anything. The power of having so much knowledge and information at your fingertips carries a truly seductive appeal – just by asking Google, we can check to see if we are “right”. And nowadays the temptation to ask Generative AI to get that information for us, digested, nicely written, with possibly huge uncertainty if not errors - despite the usual ChatGPT disclaimer we too often neglect. And once we have a view, we can publish it, without hesitation, and people all over the world can access it immediately.

But we are also living in a “post-truth” world filled with “alternative facts”. A world where bots and boiler-rooms manipulate the information we consume on social media. A world where those arguing for science or reason are increasingly at risk of being out of touch with “modern reality”. A world where, as a 2019 study reported, climate change “contrarians” get 49 percent more media coverage than leading scientists, or where, as the COVID-19 pandemic evidenced, those who argue against ‘mainstream’ science are too easily qualified as “conspiratorial believers”.

What value does science have when it shares equal space with opinions, fake news, conspiracy theories, or widely held views across a community?

Science is one way that we can understand our world. Peer-reviewed, published scientific evidence proves a hypothesis – but new theories are always evolving. In other words, science offers us a window of insight that is constantly opening wider and wider.

It’s for this reason that the scientific community hesitates to name something as a fact with absolute certainty. It often takes years of converging evidence before this can happen – for example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) still rates the probability that climate change is induced by human activity at “only” 99%. The same caution applies before relating the severity of hurricanes with global warming, despite the coincidence of Hurricane Dorian in 2019 with the former months, actually June and July 2019, being - at that time - the hottest ones on record for the globe. Many heat records have been broken since, with many more hurricanes or severe climatic events, iding an increasing evidence on the causalities of such severity. Still, there has to be room to incorporate further data and evidence as it is discovered.

How does business apply science to its work?

For the past 7 years, I have been translating environmental science for businesses, especially those whose activity (food, cosmetics, fashion) depend on agriculture. So, what does science mean for a company that genuinely wants to reduce its environmental impact, and contribute to a climate neutral and nature positive world? How does it engage with science?

Firstly, and most importantly, it uses science as a leveler, which provides a common ground where everybody understands, accepts and plays by the same rules, inside the company, but also in its different “circles of influence” that range from farmers to the consumers and include its competitors.

Take this example: cows and sheep emit methane, which is more devastating to the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. It is 18 times more powerful in fact, on average, which is why methane emissions from livestock represent 5.7% of all human-induced emissions according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Feed production and processing for ruminant livestock represents another 6.5%, mostly carbon dioxide.

Now, even if this conversion factor of 18 seems to vary between temperate and tropical regions, or if methane has a limited lifetime (several years) in the atmosphere, that uncertainty is by no means a reason to exclude ruminant livestock from the urgent measures we need to take to fulfill the Paris Agreement, which set a stretch target of keeping global warming to under 1.5°C.

Indeed, livestock’s climate effect (which is larger than car traffic) won’t change dramatically even if new science brings new elements to consider.

In other words, variability around science results is never an excuse to postpone or avoid business action.

Secondly, science therefore provides business with the knowledge that can help design transformation pathways for companies. It is like a North Star. If we know what we are aiming for, we can figure out how to get there.

Such transformation pathways enable companies to reach agreed targets (in which case they are called “science-based targets”), e.g. a certain reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater use or land expansion for productive activities, ecological integrity of landscapes, achieved by a certain time.

The challenges of connecting science with decision-making

There are two key challenges that we confront when we connect science with decision-making. And this does not apply to business only.

The biggest is time. Science needs time to obtain and consolidate results. It then requires time for scientific communities to reach consensus. Then it takes time for decision-makers, governments or business, to make appropriate decisions based on that consensus. And that can mean that action is slow to respond to a threat, or comes too late to have an effect, or that solutions must be even more powerful by the time they are implemented. The COVID-19 response has been a perfect example of that challenge, where the urgency of the situation called for rapid decisions at national and global levels, whereas science didn’t have enough time to consolidate its results, let alone the everchanging nature of viruses.

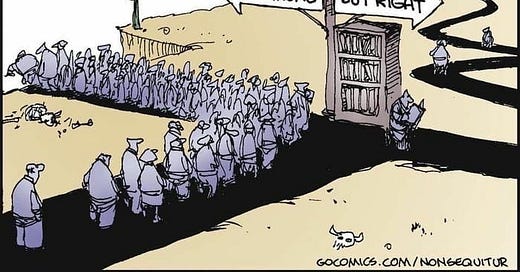

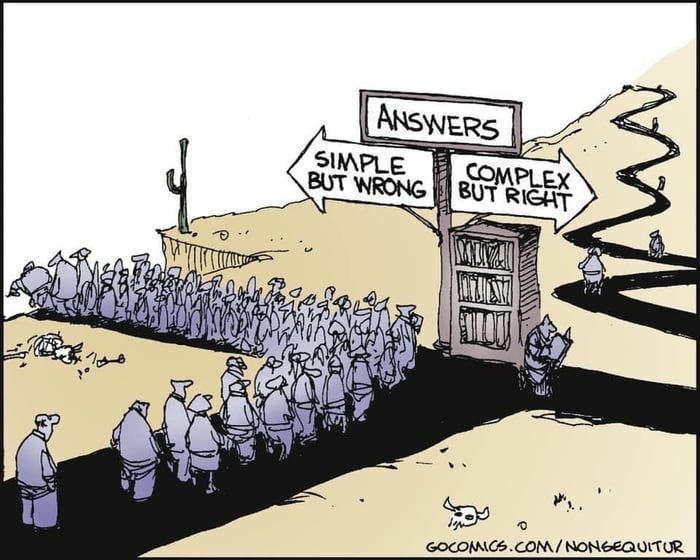

The second is the issue of consensus itself. A lack of consensus around a scientific result does not help decision-makers identify pathways to solving the challenges at the base of the issue. Business and governments will take their own views in this situation, ranging from complete buy-in to outright denial. With the risk that opinion prevails over science, or that the “simple but wrong” answer is preferred to the “complex but right”.

What I have learnt from this journey at the crossroads of science and business

There is much more to be done here – science and business must work closely together as partners on our environmental challenges. We need more dialogue to develop mutual understanding and trust. And we need a recognition that science must guide business towards solutions as much as business must guide science towards operable and actionable methods and approaches. The same applies to governments on mobilizing science to guide their decision.

Engaging with various companies, among the most progressive ones on transforming our economy to one that cares for both our planet and people, has been an amazing and enlightening experience. I have experienced an increasing interest in and call for science to guide companies transformation, when not to invent a new economy, more restorative and regenerative, less driven by only financial interests.

It leaves me even more convinced today that business can drive the urgent changes we need to make happen to keep our planet inhabitable for our children and grandchildren.

This piece is adapted from the original one, initially published as a WBCSD Insight in September 2019 https://www.wbcsd.org/Overview/News-Insights/WBCSD-insights/What-science-means-for-business

Please share your comments and experiences on how business engages with science !